Three Perfect Days Jordan

Hemispheres, September 2022

You’ve traveled to Jordan countless times from your living room—trekking across the Wadi Rum desert with T.E. Lawrence and C-3PO, snaking along an undulating mountain path to Petra with Indiana Jones. But as good as this progressive Middle Eastern country looks on screen, it’s even more of a stunner in person. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is roughly the size of Maine, but its 34,4445 square miles pack quite the punch. There are pristine Roman ruins, a red-sand desert, a thriving metropolis, a secret city carved from sandstone, and a sea with healing powers. The word “abundant” comes to mind: an abundance of beauty and history, of kindness, of sustenance. Here, every meal seems like a feast, a reason to celebrate. Come, and you’ll understand why.

Day 1

Roman ruins, a women’s cooperative, and vintage vehicles in Jerach and Amman

The sun beams like a laser into our room at The Ritz-Carlton, Amman when I pull back the curtains just after 7 a.m. Calder, my 9-year-old son, rubs his eyes and takes in the sea of boxy, white-and- tan buildings surrounding us. “They look like Lego houses,” he says.

We’re starting our day exploring buildings much more ancient than Lego in Jerash, a city just 45 minutes north of Amman that’s home to arguably the best preserved Roman ruins outside of, well, Rome. After date yogurt and croissants on the hotel terrace, we meet our driver, Hatem Zaàl, and our guide, Mohammad Bani Nasr, and head out.

Like Rome, Amman was initially built on seven hills (jebels); today, the city of nearly 4 million people stretches out over 19 of them. It feels endless, but soon the hustle and bustle gives way to olive orchards and flower nurseries; it’s much lusher here than I imagined for a country that’s 75 percent desert. Zaàl pulls off to the side of the road, gets out of the van, and returns two minutes later with two bags filled with ping-pong-ball-size red and yellow plums, which we devour, the juice dribbling down our chins.

When we reach the Archaeological Site of Jerash, we put on our hats and sunglasses and stroll through the imposing 42-foot-high Hadrian’s Arch and into the ancient city. “The old name for Jerash is Gerasa, and it means the big wall,” Nasr says. I’ve been to Athens and Rome, and I’m honestly amazed by how big this site is—and also how uncrowded. Why aren’t more people climbing the steps to the Temple of Zeus or posing for pictures in front of the Temple of Artemis, which is flanked by 11 original Corinthian columns that twinkle golden in the sunlight?

For Calder, it’s a 2,000-year-old playground. He leaps across broken pillars, pets a statue of a deer in what was once a butcher shop, and climbs to the very top of the perfectly preserved two-tiered South Theatre. I get dizzy following him up the steep steps (this place fits 5,000 people), but when I take a seat in the very last row, I’m rewarded with a dual bagpipe performance, oddly, of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” below. The acoustics are incredible.

We’re hot and hungry, so thankfully it’s just a five-minute drive to Beit Khairat Souf, a restaurant, shop, and community hub that launched in 2016 as an initiative to help local women support themselves. One of them, Hatia Bani Mustfa, greets us by handing Calder a piece of lettuce to feed the roosters, and then leads us into the shop, which is filled with artisanal handicrafts, spices, and food products. “Do you want to dress like a Jordan woman?” she asks me. Next thing I know, I’m wearing a beautifully embroidered red-and-black abaya, and Calder is donning a kaffi-yeh. Mustfa clasps a beaded necklace around my neck to complete the look. “A gift,” she says. “Just ‘like’ us on Facebook.” She takes my phone, finds the page, and, when I nod OK, taps the “like” button.

For lunch, we’re having mansaf, Jordan’s national dish of lamb and rice cooked in a sauce made with jameed (dried yogurt). It’s served in a huge platter lined with shrak, a tortilla-thin bread, and sprinkled with almonds and herbs. “We have this at every big event,” Nasr says. “You only eat what is right in front of you, and we usually use our hands.” He picks up a fork and smiles. “But today…” We dig in, loving every tangy, meaty bite, which we wash down with fresh hibiscus juice. An orange tabby and her kitten slink under the table, begging for scraps, and Calder sneaks them a few bites.

From here, it’s back to Amman to visit a place any 9-year-old boy would love: The Royal Automobile Museum. King Abdullah II established the museum in 2003 as a tribute to his father, King Hussein, who was quite the collector; now there are 80 cars and motorcycles on display, and together they end up telling a personal history of the royal family and the country’s role in global pop culture. We ogle a 1968 Rolls-Royce Phantom V that was initially made for King Hussein’s mother and a 1994 Land Rover Defender that Pope Francis rode in during his 2014 visit. I geek out over a speeder from The Rise of Skywalker, which was filmed in Wadi Rum, and Calder takes a selfie in front of the bike from Tron.

It’s just after 4 p.m., and the day’s heat has simmered, so we quickly swing by the Amman Citadel. Located on the city’s highest hill, the site has been populated since the Bronze Age—by the Ammonites, the Greeks, the Romans, the Umayyads. Aside from the amazing view of the city, we’re most taken by three giant stone fingers, together about the size of a La-Z-Boy, that once belonged to a statue of Hercules built during Marcus Aurelius’s occupation of the area.

Though we just got a good look at Amman, I don’t feel like I have much of a handle on its people, so we head to the Jabal al-Weibdeh neighborhood to meet with Anas Amarneh. “This was always the destination for artists and poets,” he says, as he leads us down the neighborhood’s winding, hilly streets, past punchy street art and trees cloaked in fragrant jasmine vines. Amarneh and his sister, Lana, launched the tour company Through Local Eyes with the goal of showing people there’s more beyond Amman’s tourist sites. “I grew up thinking Amman was a confusing city, but as I got older I realized I needed to tell the story.”

We pop into a hip cultural center, Jadal, where young adults are playing chess and drinking tea, then mosey over to Darat al Funun—The Khalid Shoman Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to Arab art, where we take in an eco- focused group exhibit called Re-Rooting. “With the art scene in Amman, we’ve seen a rise up in the last 10 years,” Amarneh says. “It’s definitely connected to the Arab Spring. We managed to have a positive experience, and this reflects on the art scene. The energy is there; the passion is there.”

We bid Amarneh farewell and walk down Rainbow Street to dinner at Sufra, in a lovely old villa with an idyllic backyard garden (bubbling fountain, blooming olean- der trees). The dishes come quickly, and each is more delicious than the last: thick and rich hummus, crispy fattoush, fire-blistered flat- bread, grilled nabulsi cheese, bite-size falafel, chicken with caramelized onions and toasted almonds. We sip blended mint lemonade, which I decide I must have every day henceforth. A dessert of pistachio ice cream topped with halva comes just as the call to prayer is broadcast through the city. It washes over us, like the voice is coming from all directions. Calder and I put down our spoons and listen, fascinated. I look around and notice everyone else is eating and laughing, unfazed. It’s just a regular Tuesday for them. For us, it’s one we’ll never forget.

Day 2

Marveling at Petra’s splendor and learning to cook in Wadi Musa

No rays of sun are beaming into our room this morning. We’re up early—so early that Calder promptly falls back asleep when we get in the van. That’s a good thing, because he’s going to need all of his energy for a day exploring Petra.

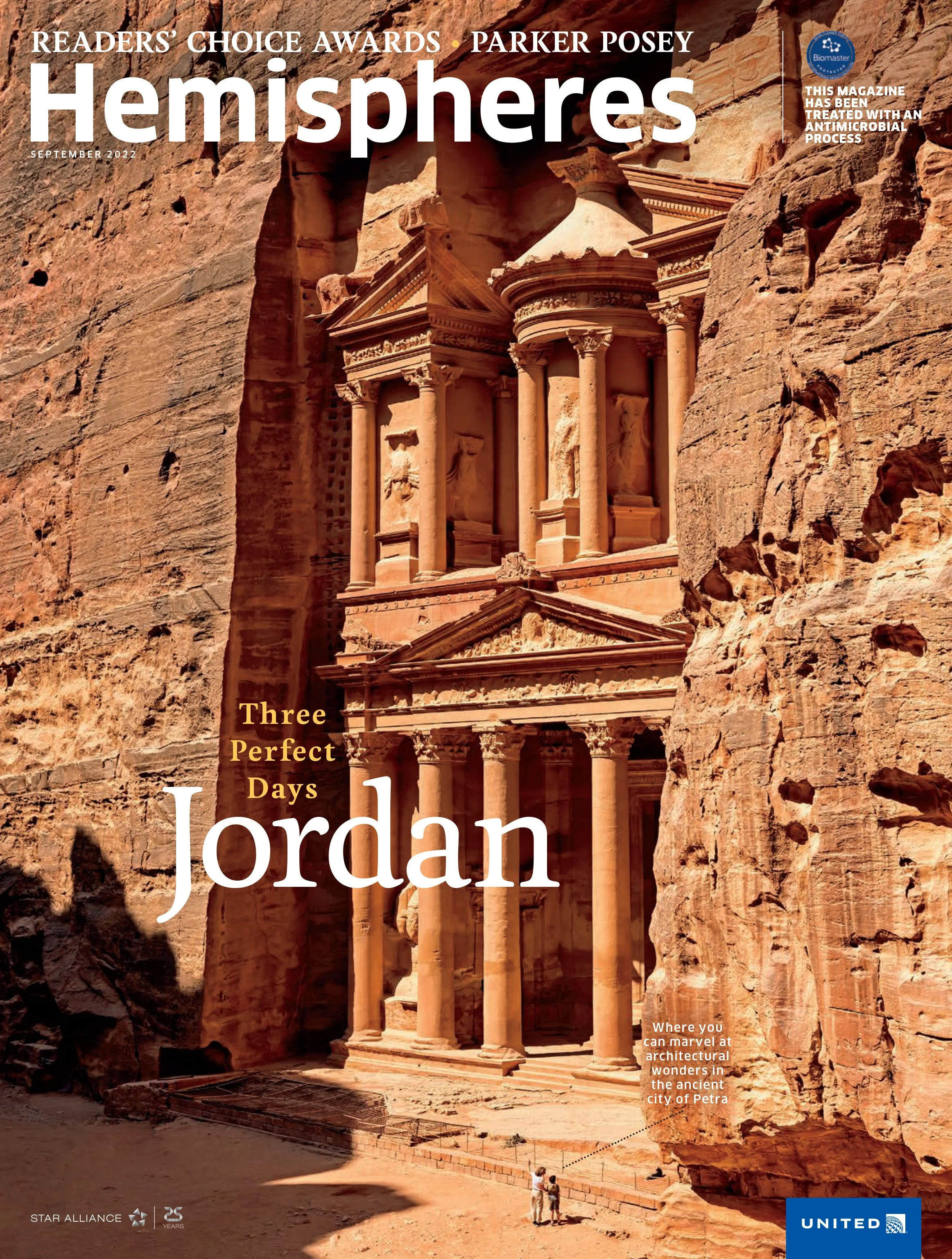

In 2007, Petra was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, and it’s Jordan’s number one tourist draw—with many of those visitors coming specifically to see where Indy found the holy grail in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. The historic site was “discovered” in 1812 by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, who, after hearing rumors of a lost city, disguised himself as an Arab traveler to avoid, as he wrote in his journal, “suspicions that I was a magician in search of treasures.” What he found was a Nabataean capital complete with temples, tombs, and caves carved in sandstone—what the poet John William Burgon described in 1845 as “a rose-red city half as old as time.”

Even though I’ve seen countless pictures of Petra, and even though we rewatched Last Crusade last week, I’m still in awe when we emerge from the final stretch of the Siq— the winding, 80-meter-high rock corridor that leads to the city—and see the iconic, elaborately carved facade of the Treasury. How in the world? I think, much as I did when I visited Machu Picchu.

“I’ve been here, oh, 15,000 times,” Nasr says, laughing, when he sees the wonder on our faces. “The first time I was 12, and it was amazing. The first time I came as a tour guide was strange, because I knew the sites, but I had to explain to people what they were.”

He does just that for us, pointing out how there are footholds along the side of the Treasury, so stoneworkers could climb up and carve from top to bottom; how many believe those carvings represent a calendar; how the building served as a tomb for the Nabataean king and countless others. A boy no older than 12 or 13 interrupts our history lesson. “Do you want to go up there?” he asks, pointing to an overlook where every travel influencer I follow on Instagram has obviously been. His name is Abat, and for 10 dinar he leads us up to the cave-like viewing platform, which is outfitted with rugs and even a hookah. Selfies commence.

Back at ground level, we continue exploring. The site is more than 100 square miles, Nasr explains, but scholars think more than 70 percent of it is underground. One pink-rock hill is dotted with dozens of doors leading into cave homes that were probably pretty nice at the time. “About the size of our apartment,” I note to Calder when we scramble into one. We stop at the High Point of Sacrifice, where many sheep gave their lives. “Do they still do it?” Calder asks. “They just sacrifice little boys who don’t behave,” Nasr says with a wink. While we’re wandering the ruins of the Palace of the Pharaoh’s Daughter, Abat meanders by atop a camel. “Hey guys!” he shouts and waves.

Finally, after a Twix break (you can buy everything from camel-printed pants to Häagen-Dazs bars from the Bedouin vendors who have tables set up all over the place), we’re ready to make the ascent to the Monastery, Petra’s other iconic monument. It’s nearly 1,000 uneven, rocky steps up, and Calder is already tired, so we decide to give ascent-by- donkey a try. No dice. After five minutes, Calder hops off, too frightened by his donkey’s living-on-the-edge footwork. So we walk. Are there tears? Yes. But there’s also a sweet Bedouin man who gives Calder a Gatorade and tells me to pay on my way back down.

We both feel a sense of accomplishment when we reach the final step and see the majesty of the Monastery emerging from the stone. Just kidding—Calder is still mad at me. We sit for a while in the shade of a cave overlook and pass the Gatorade back and forth. Our plastic bottle of salvation.

After trekking back down, we reward ourselves with a late buffet lunch at The Basin, the site’s one air-conditioned restaurant. Calder polishes off a whole plate of pasta, I dig into chicken and rice and salad, and we both down our tart mint lemonades. We’re renewed!

Eventually we make our way back to the Treasury, where we arrange a golf cart ride back to the site’s main entrance. (It feels like cheating, but I’m OK with that.) Thankfully, our hotel, the splendid Mövenpick Resort Petra, is just across the street from the access point. We check into our spacious

room, change into swimsuits, and head down to the pool for a quick dip before dinner.

We’re making our own meal tonight—sort of. We’ve signed up for a cooking class just down the road at Petra Kitchen, where we’re joined by two other travelers from New York, Huanyu and Qun. Our chef-teachers, Raed Hasanat and Reda Al Jazzar, greet us and immediately put us to work chopping veggies. “I have no idea what I’m doing!” Huanyu says, as he haphazardly goes at a cucumber. “Like this,” Hasanat says, showing him a method, and then he gives Calder some carrots and a huge knife. Thank goodness we cook a lot at home.

Our first finished dish is a tahini salad, and Hasanat gives each of us spoons to try the dressing. “It’s perfect,” Calder says. “One more grain of salt would be too much.” We all agree and then go back to chopping smoked eggplants for baba ganoush, mincing parsley for a lentil soup called shorbat adas, and squeezing lemons for fattoush. We roll out dough for manakeesh topped with za’atar and a feta-like cheese called akkawi and all get flour on our noses and laugh. Finally, we sit down to eat.

“We made all this!” Qun exclaims. “I think it tastes even better because we made it ourselves,” Calder adds, biting into a second manakeesh. Just when we think our bellies will burst, Hasanat brings out dessert—kunafa, crispy, wispy pastries with a sweet cheese filling. We didn’t make these, but that doesn’t stop us from eating all of them.

Once again, I’m glad our hotel is close by, because Calder and I just about pass out as soon as we make it to our room. “You hiked to the Monastery,” I tell him. “And you made dinner.” He smiles. “And tomorrow I get to ride a camel, right?” he asks. His eyes flutter shut before I can say yes.

Day 3

Exploring the Wadi Rum desert via train, camel, and pickup truck

After pastries, melon, and fresh dates from the Mövenpick’s epic breakfast buffet, we hit the road—and then promptly pull over at a lookout to look at… nothing. “That’s why Petra is called the hidden city,” Nasr says. The city is completely cloaked by the mountains, as if it were never there: Brigadoon in the desert.

Speaking of the desert, we’re off to Wadi Rum to get our Lawrence of Arabia on. Lawrence, the renegade British officer, spent weeks in the Wadi Rum desert during the Arab Revolt in 1917, but we’ve only got one day. Our first stop is the Hejaz Railway, to see a refurbished locomotive from the early 20th century, much like the ones run by the Turks that Lawrence and Prince Faisal hijacked. Calder climbs on and pretends to attack. (We watched the movie four days ago, so it’s pretty fresh.) If only he were wearing white robes and brandishing a sword.

Soon enough we reach the Wadi Rum Visitor Center—framed by the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a rock formation named for Lawrence’s book—which all visitors must pass through. I’m not expecting good food in the restaurant, but then I notice the walls are covered with posters for movies and TV shows filmed in Wadi Rum—Moon Knight, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen—and each says “Catering by FoodEx” at the bottom. I eat a chicken shawarma and wonder how many Matt Damon enjoyed while filming The Martian.

Now it’s time for camels. We meet our herder, Shabula, a couple of miles from the visitor center, and after saying hi to our new furry friends—mine is named Shahim, and Calder’s is Zaki—we climb aboard. (I immediately regret wearing a dress rather than pants.) We plod along under the hot sun, but Calder is beaming. “This is way better than riding a donkey!” he shouts. Shabula, meanwhile, spends the entire time talking on his cell phone, just like a New York cab driver; it makes me feel at home. The ride is oddly comfy, and a great way to take in the cinematic setting. Looking left, I can picture Rey and Chewbacca blasting away at stormtroopers on the planet of Pasaana in The Rise of Skywalker; looking right, I imagine Timothée Chalamet running from a sand worm on Arrakis in Dune.

After about 30 minutes, we trade our camels for a pickup truck whose cargo bed has been outfitted with benches—and an awning, thank goodness, because the sun is no joke. I’m reminded of Lawrence’s description of the heat, which, he wrote, “came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless.”

We put our suitcases in the cab and set off. “Hold onto your butts!” Calder says as we bounce over the sand, even though Jurassic Park was obviously not filmed in Wadi Rum. We stop at a Bedouin tent where some men are drinking tea. “If a Bedouin offers you tea, you have to take it,” Nasr advises. One does, and we do. After saying shukran, we climb up a steep sand dune so Calder can roll back down. “I have sand… everywhere,” he says with a sweaty grin.

Next, we pull up to a canyon that looks unremarkable from the outside. An information placard, however, informs us that Khazali Siq is something special indeed. We cautiously work our way down a narrow path that reminds me of an Arizona slot canyon, except the rock walls bear Nabataean, Kufic, and Thamudic inscriptions, as well as petroglyphs of camels, horses, and people. The records of multiple civilizations, across thousands of years, all on one wall, are amazing—like the ultimate bathroom-stall graffiti.

Exhaustion is setting in, so we drive to our final stop, Memories Aicha Luxury Camp, a collection of 55 tents and domed bubble suites that look like they belong on Mars. We’ve done some glamping in our days, but this takes the cake. Our tent is decorated beautifully, with an ornately carved wooden headboard, a gilded chaise longue, a chandelier, and, best of all, air-conditioning. We pass out for a bit but rally in time to watch a couple of the camp’s cooks pull our dinner from the ground—literally. Zarb is a traditional Bedouin barbecue in which meats are cooked slowly for several hours on a tiered tea tray–like contraption in a coal-filled pit; this one is massive, piled high with lamb, chicken, and veggies. One of the cooks tears off a chicken leg and hands it to me. “Holy moly,” I say. A couple of cats congregate, hoping they can steal a bite, but I’m not sharing.

The sunset is casting an orange glow over the already ruddy desert, and we head to the dining tent to chow down on the zarb, plus salad and a few mini desserts, including honey cake and a panna cotta–like pudding. Stars are starting to dot the sky by the time we finish, and we join a dozen other guests around a bonfire outside. One family is from Mexico, another from Italy; there’s a couple from Long Island and another from D.C. I ask the group what brought them to Jordan. “Instagram,” says the Italian lady. “Yeah, social media,” agrees the Long Islander. One thing’s for sure—no social post could capture the beauty of this night’s sky. Calder and I stare upward, both of us taking in the Milky Way for the first time, shocked by how accurate its name is.

Finally, it’s time for bed. We walk back to our tent, only to discover that Calder seems to have lost the key. While I was talking to the other guests, he’d been jumping from the stairs into the sand, and it must have fallen out of his pocket. I’m irritated, but it can’t be helped. We turn around and head back in the darkness, with only a few soft globe lanterns lighting the way. Calder reaches out and takes my hand, and any annoyance I feel immediately disappears. How can I be anything but grateful right now, here with my child, in a magical desert, under a sea of stars brighter than any I’ve ever seen?

We make it back to the bonfire, which is now flickering softly in the cool breeze, and Calder starts digging around in the sand. “Found it!” he calls.

And we walk back again. Slower this time. Not wanting the night, or the trip, to end.